Was Jim Carlson the Criminal or Victim of Synthetic Marijuana Sales Prosecution?

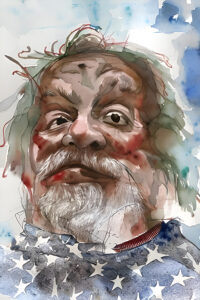

Living in an apartment above a smoke shop would be a dream come true for some, but for Jim Carlson, it’s an ironic reminder of his recent past. Carlson, 64, is currently on house arrest, a consequence of being found guilty of selling synthetic marijuana, more commonly known as “spice.”

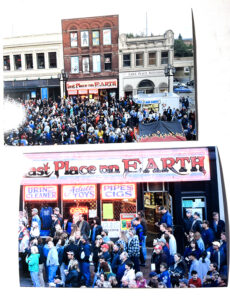

In 2013, Jim Carlson, who brazenly ran the Last Place on Earth smoke shop in Duluth, Minnesota, despite several police raids, was found guilty in federal court on 51 out of 55 charges. These included multiple counts of distributing and selling improperly labeled synthetic drugs. As punishment, he was given a 17 and a half year prison sentence, followed by three years of supervised release, and was ordered to pay a $25,000 fine. In addition, Senior U.S. District Judge David Doty issued a $6.5 million forfeiture order, which allowed the authorities to confiscate the shop, its bank accounts, and other assets.

Former Duluth police chief Gordon Ramsay has stated that Carlson was the “largest synthetic drug retailer” in the country. Ramsay tried to talk to Carlson about the adverse effects of his actions on neighboring businesses and innocent people, asking him to stop, but Carlson remained defiant. As a result, Ramsey claims downtown police calls were incessant, and hospitals were overloaded with synthetic drug users experiencing hazardous side effects.

While being held at the Milan Federal Correctional Institution, Carlson was interviewed about his case by a local television news channel. During the segment, Carlson remained steadfast in his belief that he was wrongly accused and targeted for his opposition to authority.

When asked by the reporter if he was a “bad guy,” Carlson replied, “I don’t think so.”

And that’s putting it mildly.

Carlson’s family has a legacy of fighting for constitutional rights, which influenced his own beliefs. In the 1960s, his father owned a chain of adult bookstores in Minnesota and frequently clashed with authorities over obscenity laws, resulting in regular police raids on his businesses.

“They’d take stuff and he’d fill the shelves back up again. He’d end up in court, and sometimes he’d go to jail. On appeals, it would be ruled that he didn’t violate any laws,” says Carlson who worked in the family business as a teenager and eventually managed the finances before opening The Last Place on Earth in 1982.

Starting with a $3,000 stake, Carlson stocked his “head shop” with smoking accessories, t-shirts, posters, incense, tapestries, and even martial arts gear. The business was successful, and during the days of Operation Pipe Dream, caught the attention of authorities. Carlson recalls the day two semis pulled up to his door and so much supposedly illegal merchandise was confiscated that it had to be stored at the local armory rather than the police station.

“I fought it in court and I ended up winning. Even when they were going to give me eight years for selling paraphernalia, I didn’t cave,” Carlson says. “I’m a firm believer that marijuana is a lot better than alcohol and, and other drugs out there because it has medicinal purposes.”

To minimize any further potential legal issues, Carlson’s attorney advised him to begin selling cigarettes and tobacco products. The move was aimed at proving that the store’s merchandise was intended for tobacco usage rather than for cannabis-related purposes. Carlson consented and sold the tobacco items at the minimum rate permitted by the state.

“I’m not fond of cigarettes because I’ve had a lot of friends die of cancer,” he says. “Selling cigarettes and rolling supplies to customers [many of whom were homeless or low income] I felt like I was killing them. On the other hand, they were addicted and they were buying the shit, so I sold it at a low price where they weren’t getting gouged.”

A new designer drug, “K2 spice”, made the scene in the early 2000s. It is believed to have been first synthesized by John W. Huffman, a professor of organic chemistry at Clemson University, who was researching the effects of cannabinoids on the brain and created hundreds of synthetic compounds to study their effects. One of these compounds, JWH-018, was eventually used to make K2 spice, which found its way onto the streets and was sold online and at smoke shops as a legal alternative to marijuana.

One fateful day, Carlson’s phone rang with a call from a smoke shop colleague who said she was selling a ton of the stuff. Even though he didn’t know much about it, he told her that the product was priced so outrageously that no sane person in his area would buy it.

Or so he thought.

On the agreement that he’d get his money back if it didn’t sell, Carlson agreed to buy two packages of spice. Word got out, and before the order even arrived, people were ready to put down $30 a gram, double what he’d paid. He sold out within a couple hours and quickly ordered more.

“I sold it for two months without an issue. I had neighbors selling it too. Then one store in town got broken into. The crime reporter was looking at the police report wondering why somebody stole ‘incense’ when there were more valuable things on the shelves. The cop supposedly looked at him and said, ‘Are you retarded? “It’s fake marijuana.”

The next day headlines on the front page of the local paper were all about all the smoke shops in town selling a legal form of pot. “For months we didn’t have any issues with it – it was just a normal business deal,” Carlson says. “As soon as the news got out, I had lines of people waiting to get into my store to buy this stuff.”

Carlson quickly became the face of spice. He was interviewed as part of three documentaries detailing the war on synthetic drugs, including one report by MSNBC. He recalls attending legitimate B2B trade shows at the time, where K2 was openly for sale, complete with price sheets and samples. “How much more legal could it be?” he thought at the time.

Carlson defends his actions, stating that the version he was selling wasn’t the “super duper knock you on your butt stuff.”

Multiple authority figures, including a judge and a DEA spokesman, assured Carlson that he was in the right. The city of Duluth even offered to sell him a license so he could sell K2 just like tobacco. Unfortunately, the feds had another opinion. A slew of cases were filed using the Reagan-era drug statute known as the Analogue Act, and in the fall of 2012, they came knocking on Carlson’s door.

“Forty-two agents armed with assault rifles jumped off a city bus, threw my customers and workers on the ground and hog tied their hands behind their backs,” Carlson recalls.

The U.S. Attorney’s office said at the time that the raid was part of a “broader investigation.” It included Duluth police, members of the Lake Superior Drug and Gang Task Force and Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) agents.

The subsequent trial in U.S. District Court in Minneapolis, lasted seven weeks. Carlson faced multiple federal charges, including selling misbranded drugs and controlled substance analogues. The conviction stood because prosecutors were able to prove through circumstantial evidence that Carlson knew his spice products were illegal. An appellate ruling in 2016 upheld his conviction.

To this day, Carlson remains convinced he was railroaded.

“I didn’t make this stuff. I was a retailer. I bought it from other people. The FDA even got up in court and said that the manufacturer, not the retailer, is responsible for labeling,” Carlson states.

“They took my store and everything that I worked 40 years for, and gave me a 20 year sentence. There were guys that murdered people and molested little kids that got less time than me,” Carlson adds.

Carlson claims that the judge did disallow evidence showing how he had been specifically informed by people in authority that he was not engaged in any illegal activity. Additionally, the judge denied Carlson’s request to use the advice-of-counsel defense, which asserts that a defendant who reasonably relies on the advice of a legal counsel may not be convicted of a crime that involves willful and unlawful intent. Carlson further asserts that he consulted with eight attorneys who were aware of the facts and advised him that his actions were legal.

It wasn’t until AFTER the jury came back with their guilty verdict, that things got really interesting. One juror told the Duluth News Tribune that he was surprised by how weak the prosecution’s instructions had been when it came to defining what was and wasn’t legal, and that he now had misgivings about putting a guy away for something that was legal. “I’m not convinced that (Carlson) did anything wrong,” the juror said. “I don’t think the government said enough.”

“We agreed that (Carlson) didn’t think he was breaking the law,” he added. “We always thought he thought he was doing the right thing.”

“That tells you right there that the whole thing was a sham,” Carlson says. “I had attorneys guarantee me that I would never spend time in prison and that they’d never get my money. In hindsight, they downright said we had a bad judge who didn’t pay attention to the constitution.”

At the time, Carlson was baffled by the fact he seemed to have been singled out, when other stores in his neighborhood were selling spice without any negative repercussions at all.

“Never once did they even get questioned. They continued selling it when I was getting raided and [authorities] shut my store down.”

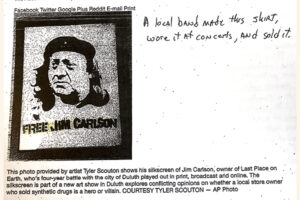

In retrospect, Carlson has an idea why he was made an example –- he ran for President and was a vocal proponent of legalizing marijuana. In 2012, he was placed on the Minnesota ballot by the Grassroots Party and his name was positioned between Barack Obama and Mitt Romney. The Grassroots Party also distributed a flier featuring a map of the state with marijuana leaves and accused “witch-hunting politicians” of trying to eliminate Carlson’s business, stating that “Mr. Carlson is fighting back.”

“I’ve said all along that the substance needs to be regulated,” Carlson stated. “I also argued that if marijuana were to be legalized, who would even consider buying the synthetic version?”

“I had so many customers, a judge ordered that I had to pay two police officers $42,000 a month to stand in front of my store for 14 hours a day to manage the crowd,” he adds.

Carlson believes another reason he was targeted was that liens placed on his bank accounts following a previous raid prevented him from accepting credit cards, leading to an abundance of cash on the premises. During raids conducted by federal and city agents, Carlson alleges that over $2 million mysteriously disappeared, with the surveillance cameras shut down to prevent any evidence from being captured. Furthermore, he claims that an investigative reporter who was covering the situation was found dead with a bullet hole in his head at the rendezvous location where he was meeting his informant.

Carlson maintains that his motivation for continuing to sell it was not purely financial. He genuinely believes that he was helping customers who suffered from medical conditions, such as Parkinson’s disease and the adverse effects of cancer treatments, by providing access to a healing herb, even if it was in its novel form.

Still, you have to ask: Looking back, was it worth it to sell a product that was at least questionable in terms of legality as well as safety to consumers? And what was the real crime in this situation?

“It sure wasn’t worth going to prison and losing 90 percent of everything I owned,” Carlson says. “I believed that what I was doing was legal, but I was shocked to discover how much a judge could circumvent the constitution and not allow the jury to hear the truth. I’m a strong believer that this country abides by the constitution. . . just not in my case.”