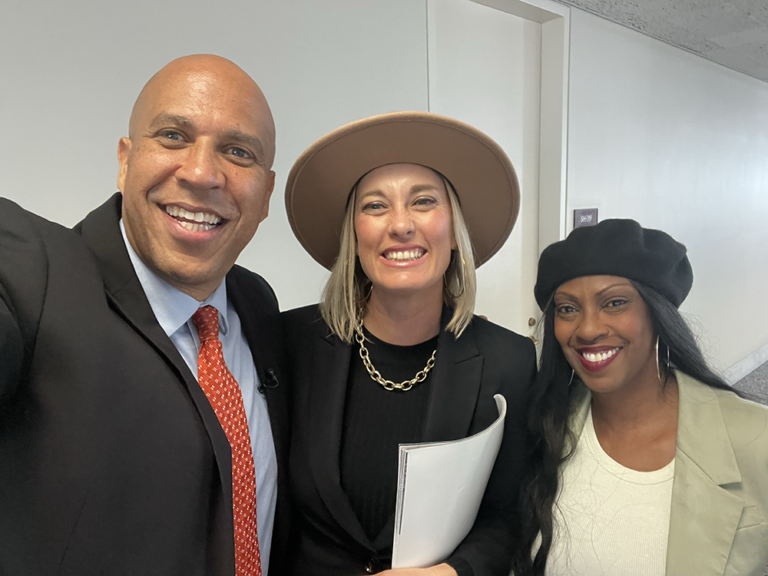

The Last Prisoner Project's Director of Advocacy Tells Her Story

The courtroom is full, and the people are waiting. They’re eager to see the next exhibit: a poster board featuring a lineup of the hardened criminals they’ve been hearing about during the proceedings, a long-awaited photo array of real-life gangsters involved in a drug-trafficking scheme so extensive, it propelled an uninterrupted supply of marijuana across New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut. With how much money and how many years this went on, with goons and lookouts and distributors from here to kingdom come, it seemed certain the next Al Capone and his grizzly band of henchmen were about to have their sneering faces displayed before the rapt audience in that New York City courtroom.

Instead, what they got was a mugshot matrix of 15 men grimacing in anxiety, belabored by fragile psyches waiting to sing like canaries on their cohorts. That is, all except for one—the sole woman among them.

And she was smiling.

“I’m not going to have a bad picture,” Stephanie Shepard, Director of Advocacy for the Last Prisoner Project laughs into the phone. “That’s not how I was raised.”

But the smile was more than just posturing. Stephanie, facing a charge of conspiracy to distribute 1000 or more kilograms of marijuana, had never been in any sort of drug trouble in her life. Raised by loving parents in the suburbs of California, she’d never felt the threat of hard times, never had an agent flash a badge at her doorstep before pressing deep into her home.

The one way I can describe prison is visually neutral. Everything we’re issued, everything that surrounds us is beige, gray, khaki green, and brown . . . Color brings creativity and happiness and so much to your life that you can’t possibly understand until it’s taken from you.

Stephanie SHepard

She could smile the day of her arrest because surely an educated young woman with the habit of good manners would find an understanding officiant helming the gavel, especially knowing the charges were baseless. Even if they could pin something on her, ten years to life in prison for a first-time offender? Laughable. But when that gavel dropped and she was sentenced to a decade in federal prison for her affiliation with a man whose drug-running peons called a “manipulator” and “puppeteer” while under interrogation, her life as a “daddy’s girl from the ’burbs” dissolved. With each shell-shocked step she took down the underground corridors connecting the brutalist architecture of a U.S. district courtroom to the frigid holding cells in the bowels of 500 Pearl Street, Stephanie ceased to worry about her own fate—that much had just been sealed—and instead, her mind turned to the pain she’d just wrought on the family who worked hard to raise her right. Awaiting transport to federal prison, she thought of her father, at the time 91 and “my everything,” whose little girl was just whisked away to God knows where for longer than he’d remain on Earth.

“The one way I can describe prison is visually neutral,” Stephanie says, conjuring images of The Federal Correctional Institution of Danbury, CT. “Everything we’re issued, everything that surrounds us is beige, gray, khaki green, and brown.” Contrary to the vivid imagery popularized by the hit TV series “Orange Is the New Black” which, fun fact, was authored by Piper Kerman after her time spent at the federal prison camp in Danbury “right down the hill from us,” Shepard describes a world dulled by shades far more subdued. “Color brings joy,” she says of the psychology behind the drab backdrop. “Color brings creativity and happiness and so much to your life that you can’t possibly understand until it’s taken from you.”

The scene was a world away from Stephanie’s life months prior where, upon entry into her tony Williamsburg apartment, a view of the NYC skyline ensconced the chic interior, replete with careful art that peacocked alongside pristine white furniture and imparted a “welcome to the good life” reception to all who entered. “My friends would refer to it as The Snow Globe,” she says, noting its place at the top of the building and how it was primarily comprised of oversized windows.

It was there that she hosted gatherings and entertained her inner circle of friends, including the blue-eyed quiet type she was introduced to as Connor. The pair met at a mutual friend’s barbeque—“He was selling weed.”—and exchanged numbers when she was still new to the city. Soon after, when she discovered the lease on her first apartment wasn’t up for renewal, Connor offered to let her stay at his place for a while “above an art store on Metropolitan,” until she eventually moved herself into The Snow Globe.

He used to have a bunch of fake IDs and I would look at them and laugh and say, ‘Gosh, is your name even Connor?’

Stephanie SHepard

“It should have been a red flag,” she says, admitting that they’d only met two weeks beforehand, but his charm was undeniable. “He took cooking classes and was always cooking at home,” she says. “He was a foodie, so we ate at the best restaurants in New York.” Per court documents, the pair were an item for the better part of three years. She knew he was a dealer. But marijuana—though still illegal—wasn’t regarded as that big a deal. He was moving serious weight, but she was unaware, and therefore, never properly gauged the risk. She ignored, however, perhaps the biggest red flag of all: “He used to have a bunch of fake IDs and I would look at them and laugh and say, ‘Gosh, is your name even Connor?’” He would dodge the question with a laugh of his own.

In short order, his real identity would come to the fore.

“He eventually gets arrested, and there I am trying to find out information,” she says. “I was talking to the guy who introduced us, and I said, ‘I can’t seem to find Connor [in the system] — are you sure he got arrested?’” The mutual friend suggested she try “this name [instead] and gave me his real one.” That’s how she discovered that the introverted beau she called Connor was simply a character being played by a criminal named David.

“I found out after he was arrested that he had gotten in trouble in Seattle,” she says. “He agreed to cooperate with the cops.” He allegedly wore a wire, but when face to face with “the connect,” he intentionally exposed the wire, “then fled to Mexico.” Stephanie says, “After about a year, he turned up in Brooklyn as Connor.”

Back to all the fake IDs, “Yeah, I got caught slipping on that.” She couldn’t see it at the time, but she’d already slipped into a pit that put her in absolute and immediate peril of two federal agents, an unscrupulous trickster, and the dishonorable henchmen conscripted by all three of them.

From David’s arrest to the time she took on an attorney—“one of the attorneys for John Gotti, Jr.,” at that—the curtain was pulled and the spool of lies spun by the puppeteer unwound. At the same time, Stephanie Shepard would, for a while, cease to exist, and instead be assigned a strange new name of her own—“Crazy.”

“My paperwork says The United States of America versus Stephanie Shepard, AKA Craze, AKA Crazy,” she says, referring to the literal name of her case filed in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District Of New York. The nickname was placed upon her by Connor AKA David who, after their breakup, set out not only to paint her as insane, but to pit her against his dealers, often telling them she sold much more marijuana than they had. This not only ramped up competition among them but implicated her as part of the crime consortium—a strategic move. If he could create a bridge connecting her to his illicit affairs, she’d be forced to keep quiet when, post-breakup, at the behest of his new girl, he needed “insurance” that she wouldn’t rat him out once he cut her out of his life for good. Thus, the tactical inception of Crazy, courtesy of the Puppeteer.

Stephanie doesn’t deny that some of her lifestyle was a product of drug money. Men who deal big tend to pass along a little something to their women—it’s canon. She does deny, however, that she was pushing weight for her former lover’s enterprise. “I was a licensed real estate agent and have always had a nice car and home,” she says. “Yes, the extra money was helpful, but I had a career.” Even one of the arresting officers, Agent Christopher Quinn of the Department of Homeland Security, didn’t find anything that would implicate her when he walked into The Snow Globe the day of her arrest.

From the Official case file in the appeal of United States Of America v. Stephanie Shepard AKA Craze AKA Crazy:

Agent Quinn testified that he had never seen Shepard with any marijuana, with any money, or with any cellular telephones. When he arrested her, at her apartment on May 26, 2010, he did not see a money counter, a heat sealer, or any paraphernalia associated with the marijuana business. Agent Quinn did not attempt to get a search warrant for Shepard’s residence. He testified that, ‘We did not have any current information to show that Shepard was involved in narcotics trafficking at that point.

Essentially, her source of supply [name withheld] was arrested and incarcerated and did not have information that was current.’ He had ‘no current information that Stephanie Shepard was involved in a conspiracy—any conspiracy.

My father was born in 1919, in the Deep South, in Alabama . . . to have him deal with his youngest child being called a drug dealer, it was hard. It was so hard.

Stephanie SHepard

“They never even caught me with a joint,” Stephanie says. “But 2,300 pounds? Conspiracy?! Evil.” Not only was zero evidence of participation (AKA conspiracy) found in her apartment, there was no concrete evidence that the calls and texts to “Crazy” in David’s cellphone went to Stephanie. When investigators contacted the company that owned the line belonging to “Crazy,” they were met with the following response:

“Search results indicate one or more of the numbers listed on the above-referenced legal demand may belong to Boost, a Sprint prepaid phone service. Our office maintains subscriber information for Boost accounts, but this information is often inaccurate or incomplete.”

Her filed appeal makes note that the testimony given by David’s frightened henchmen constantly changed, repeatedly failing to corroborate or create probable timelines.

“Each of the cooperating witnesses offered sworn, inconsistent testimony that minimized his own involvement while increasing the amounts of marijuana sold by the other members of the conspiracy,” the appeal reads before launching into the myriad ways “conspiracy member” Stephanie—according to multiple men pictured on the aforementioned courtroom poster board—was simultaneously in more places than one, and in some instances, suddenly not even present depending on who was telling the tale and when.

Still, with no tangible evidence presented and an appeal that was quickly denied, Stephanie languished inside a federal prison with no way to make sense of the decade-long stretch that lay before her. More than just angry, she was embarrassed.

“I had family members who said, ‘You brought shame to our family.’” Stephanie says different opinions ran their course throughout the family, but ultimately, the only one that mattered was her father’s. She explains:

“My father was born in 1919, in the Deep South, in Alabama.” She mentions that he’d already been through so much, and “to have him deal with his youngest child being called a drug dealer, it was hard. It was so hard.”

This is the only time during our hours of dredging up these torturesome memories that Stephanie would cry. “My dad never told me he was ashamed of me—not once—and that’s who I cared about most.” She steps back from the story to correct the catch in her throat. Once collected: “As long as my dad said, ‘You’re good,’ I was good.” Besides: “The daughter my father raised was not willing to work with the government.”

Once that epiphany set in, the pain was a little more tolerable on the inside, literally and figuratively. In the meantime, Stephanie busied herself with a noble cause.

“A gentleman who ran an ESL program at the prison came and found me on day one,” she says. “He told me, ‘I’ve heard about you. You would be great. Would you be willing to teach?’” Stephanie admits she’s never taught anything in her life. “ESL was a [Federal Bureau of Prisons] requirement for Puerto Rican inmates who weren’t fluent.” For 12 cents an hour, she taught English for nine years, providing support for fellow inmates that went beyond historical knowledge and conversational proficiency. She recalls a moment with a student and cellmate that particularly moved her: “When Norma told me she was able to communicate with her [English-speaking] daughter thanks to our classes, I was like, ‘That’s it for me! That’s what I’m about!’” She laughs, delighted in the memory. “I ended up getting my teacher’s aide certification.”

Bit by bit, bright spots would appear during her incarceration—sometimes literally.

“I saw some girls with an order of beads,” she says with a sudden lift in her voice, as though experiencing it all over again. “Strands and strands of these glistening, beautiful, colored beads, the most color we could see … shiny ones, sparkly ones, things made of the very thing we were deficient of.” Something so simple and overlooked, cheap and in many cases tacky on the outside are, in the bleak walls of prison, virtual rubies and emeralds by which one could adorn herself and/or her abode. In similar form for precious gems, these glass beads cost the wearer heavily.

“Prison is expensive,” Stephanie says, referring to more than just beads. “If you want any sort of comfort, it’s really expensive.” She explains: “We buy things from the commissary and everything in the commissary has a 30 percent markup. So, you’re making 12 cents an hour,” she pauses, “then you’re paying a 30 percent markup on anything you want or need.”

Prison isn’t supposed to be enjoyable, of course. Penitence is the name of the game, but the punishment of the inside often makes its way out, a fact Stephanie deals with daily.

The simple ring of a doorbell gives her pause, and her nights are constantly interrupted by dreams of re-incarceration. There’s paranoia that her freedom will once again be taken from her. Simply making her way through traffic and having a cop pull up behind her adrenalizes her system in ways that manifest physically. She begins to sweat, her heart thunders in her chest, and her hands grip the steering wheel unnaturally tight. “It doesn’t matter that I am driving legitimately, that I have insurance, and that everything’s in place—when that officer pulls up behind me, I don’t know if that’s going to result in a violation or not.”

A violation, she explains, would send her right back to prison, as she was given a five-year probation sentence to be served upon release. She has now served four out of that five. For the next and final year, she’ll continue to report to a probation officer. If she is so much as accused of doing something wrong that would lead to an arrest, she’s back to the nightmare; back to being told when to stand for count, being told when she can eat, and back to mandatory strip-searches if she wants to see her family on visitation day.

I can hear the stress in her voice as she explains her physical reaction to something as ordinary as seeing a cop in Target. She’s been out of prison for five years by the time we have our conversation, and I can’t help but wonder how someone so patently traumatized by the experience would accept a position with The Last Prisoner Project.

Launched in 2019, The Last Prisoner Project is an organization that confronts the stark injustice of individuals serving real time for cannabis offenses, even though cannabis has been legalized in the states they offended. The coalition works alongside experts in policy, education, and drug reform and challenges the remnants of our country’s antiquated cannabis prohibition. Last Prisoner’s crusade centers on securing the release of these inmates through legal maneuvers such as clemency and resentencing. Because of this, Stephanie’s work means she’s pulled back into the world of cops, of court, of prison, of despair, of the rage and the pain of injustice. Some days, she’s doing her best to comfort someone who just might die inside a prison cell over something that can now be delivered to a doorstep in their city with a few button-presses on a delivery app. Day to day, she confronts these vile notions that still live on in her mind and cause her voice to shake when she speaks on the experience.

“Why not just leave it behind?” I ask her. Not that it’s a suggestion, but I have to know. “You could get on with your life, move into a career that has nothing to do with all the shit that triggers you and just … never look back.”

But that’s not an option for her.

“Once you’ve gone through it, you start to not think so much about yourself and you start thinking about the people coming in behind you,” she says with zero quivering in her voice now. This is conviction. “Once I got home, I had a decision to make: Was I going to be a person who just moved on, or was I going to be a part of this movement? I’m doing this for people like Parker Coleman, a young man who’s looking at 60 years. I’m doing this for Ricardo Ashmeade, who’s already served several years [of a 22-year sentence], whose daughter Richeda is now in her final year of law school because she wants to fight the situation that her father is in. This isn’t about me.”

She pauses, then gives the biggest endorsement that might exist for Stephanie Shepard: “I know if my father were here today, he would approve of what I’m fighting for. Look: I could either fight for those who are incarcerated for cannabis, or I can make what’s going on ‘not my problem.’ Thing is, my father raised a daughter who is going to make this her problem, and because of that, he would be proud of me.”

***

It took hours of time excavating horrid memories she’s endured for the past 14 years to figure it out, but I eventually understood: Stephanie Shepard isn’t running from her trauma; she’s using it to fuel the battle.

And because she gave me such a raw glimpse into what went down, from never denying that some of her life was a product of ill-gotten gains (“I accepted my part”), to refusing to falsely incriminate other people, even if it meant saving her own ass, I know why the caged bird wouldn’t sing.

It’s because the system may have taken nearly a decade and a half from Stephanie Shepard, but it damn sure didn’t take her commitment to integrity and justice—values that her father, may God rest his soul, made certain were forever etched on the heart of his youngest daughter.

By Eva Berlin Sylvestre