Did Commercialization Lead to Cannabis Prohibition?

We’ve won the argument; an overwhelming majority of Americans support federal legalization. Is it time to drop the conspiracy theories?

By Joshua Scott Hotchkin

In order to make sense of how the legal status of cannabis evolved over the past few centuries, I am going to need you to engage your imagination. This is not bexcause we lack facts, but because some of those facts were born in a context that is lost to us. When we view old facts in light of today’s world, it often gives them the appearance of arising via shady characters and nefarious deeds. But if we can set aside the biases and prejudices of our zeitgeist, it may be possible to see how the ball of marijuana prohibition got rolling from innocent, perhaps even benevolent, roots. Bear with me for this.

Imagine being given a medicinal elixir that, without your knowledge, contained marijuana.

Now, imagine being given a medicinal elixir that, without your knowledge, contained marijuana and you have never tried marijuana before.

Next, imagine being given a medicinal elixir that, without your knowledge, contained marijuana and you have never tried marijuana before, and in fact had never even heard of it before, and thus have no knowledge of its effects.

Finally, imagine being given a medicinal elixir that, without your knowledge, contained marijuana and that you have never tried marijuana before, and in fact had never even heard of it before, and thus have no knowledge of its effects, and in fact, have little to no knowledge of recreational drug use or altered states of conscious experience at all.

The first written treatise espousing the medicinal properties of cannabis to Western medicine came out in 1839, and by the 1850s it became a somewhat common ingredient in medical elixirs.

If you cannot imagine this filling you with panic, terror and a sense that you have lost your mind completely, then you are probably helplessly deficient in imagining the context in which cannabis use often occurred in the mid 1800s, when it was added to medicinal elixirs that were sold to the public with the promise of medical miracles.

The first laws to address cannabis in the United States came about in the wake of a handful of suicides related to its ingestion by people who had no idea what they were getting into. While it is difficult today to imagine marijuana causing such an extreme act, it is not necessarily difficult to imagine it in the context of a distant past in which none of the things we know today were known—and superstitious beliefs were far more prevalent. Marijuana elixirs were sold alongside those containing the highly addictive opium, which was also being added to mid-19th century medical products, and thus coloring the view of cannabis by association. Several states began to recognize a need for consumers to be informed about what they were ingesting. And so, the first cannabis laws were consumer protection regulations, which required manufacturers and sellers to label their products as containing “poison,” as this was before the average person firmly understood the concept of narcotics. Arguably, you’d be hard-pressed to find anyone, now or then, who thought it a bad idea to ensure that people knew what they were getting into before ingesting a substance with profound effects. Even states that have legalized today have strict labeling laws—and no one, save the most resolute of libertarians, disputes their validity.

And this is how the stage was set for cannabis legislation over the next century, ultimately culminating in Nixon’s anti-drug rampage in the 1970s. We have no hard evidence of evil plots or scheming madmen; just the commercialization of medicine leading to conditions in which valid concerns were eventually distorted into puritanical derangement.1

The first written treatise espousing the medicinal properties of cannabis to western medicine came out in 1839, and by the 1850s it became a somewhat common ingredient in medical elixirs. By the 1880s it had become fashionable for the upper classes to use hashish recreationally, and parlors established for its use became prevalent in cities along the east coast, similar to the opium dens of the day. The first mention of smoking the plant matter directly was a report on Mexican soldiers in 1874. Cannabis use was not exactly rare in the mid to late 19th century, but it would have still been virtually unknown to most people living in rural areas, and these are the people whom labeling laws were enacted to protect.

These were state laws; not federal. Both the federal government and the intellectuals of the day had taken the position that cannabis was mostly harmless, and that prohibition would be more harmful. However, the damage had already been done. In rural areas where most US citizens resided, cannabis had gained a reputation as a dangerous and addictive substance, which was bolstered by its usage occurring in similar manner to the more harmful opiates. A handful of cautionary tales of cannabis use gone awry was enough to color public sentiment, which created legislative momentum against it.

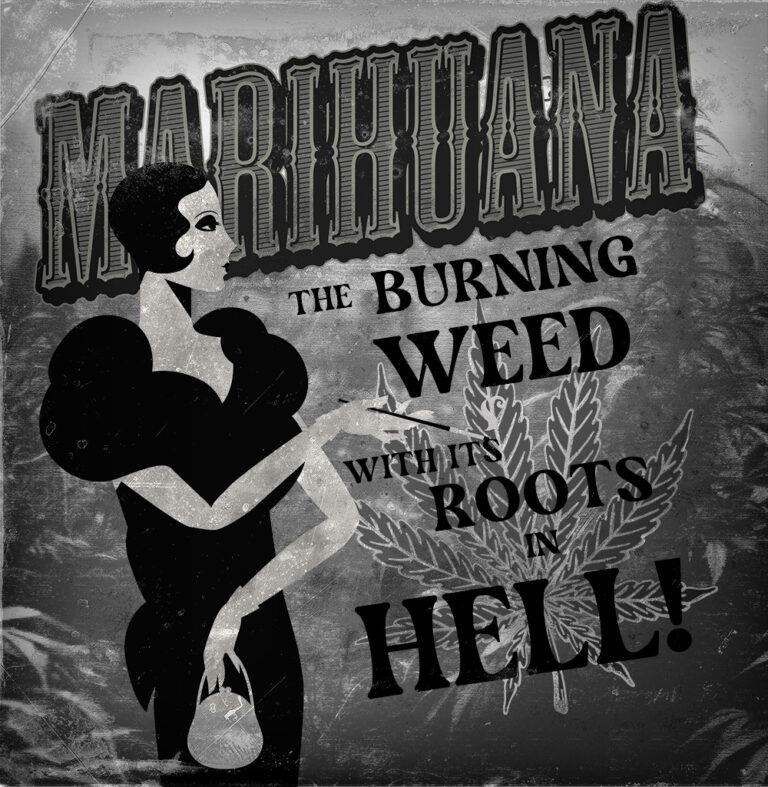

By the time Anslinger came along, cannabis was already restricted by law in several states, and a few generations of cautionary tales had warped into a puritanical hysteria which regarded it as a destructive narcotic. It did not matter that it was not true, because that is not how things work. Fear and righteous indignation have had a way of circumventing reason throughout most of human history. As time went on, cannabis became a victim of this tendency. Even so, Anslinger was powerless to do much about it. The Marijuana Tax Act of 1937 did very little except to discourage legal commerce, which then stunted further research and understanding. Yet states unanimously adopted policies of prohibition, thus paving the way for dangerous black markets which would add to public hysteria about the dangers of cannabis use.

What began as a reasonable response to irresponsible cannabis sales slowly morphed into a bias against it, and that bias was met with increasing legislation over time, which served to strengthen the perception that marijuana was dangerous and evil. A feedback loop of bias confirmation finally culminated in the Controlled Substances Act of 1970—which became the impetus for the federal government’s full out war on drugs, thus creating the largest prison population in history by the end of the 20th century.

If only the first cannabis sellers had put a warning on the label, history might have unfolded differently. The only reason this did not happen is that when medicine became business, businesses sought an advantage through trade secrets, which is still happening today. It was the impetus of profits and greed, which paved the way for disastrous attitudes and policies against a plant that is relatively harmless when used responsibly by fully informed people.

1It’s important to clarify that when we say we have no hard evidence, we mean, up until the Nixon Administration, whose malicious intent was publicly confirmed by policy advisor, John Ehrlichman:

“We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news.”