Media Lies: Navigating Reality in a Post-Truth World

What do you know about cannabis? Seriously, ask yourself that question.

Maybe you know how some strains affect you. You may know a few active ingredients. Perhaps you can explain a bit about how it functions within your body.

But there’s a chance—and not a small one—that at least some of this information is not true. That won’t come as a shock. Cannabis enthusiasts are both the most informed consumers and the ones calling loudest for more research. They accept that our best conception of cannabis is probably incomplete and might be somewhat wrong.

But what if it’s completely wrong? What if it could be proven conclusively that cannabis has no medicinal value and that every benefit brought by cannabis products was a placebo? Would anyone actually change their opinion? Probably not.

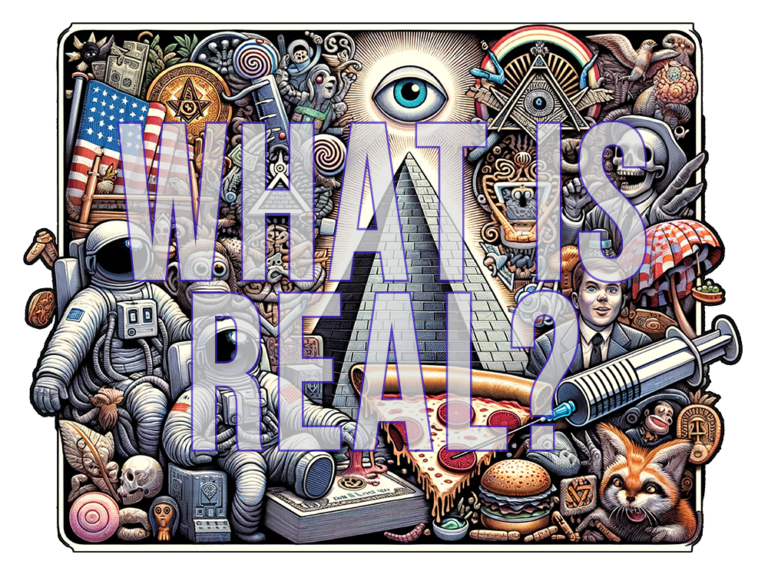

This thought experiment serves to highlight a weakness in modern society. Bombarded with endless information, we’ve largely lost our ability to discern truth from fiction, separate opinion from fact, and judge objective reality. Powerful forces have the means to hijack our emotional responses in ways that make us deny our reality so that they substitute another, more advantageous version. Just look at the evidence.

The Rise of Alternative Facts

There is no place more subject to modern reality distortion than politics. Take, for example, the day Donald Trump was sworn in as President. It was a cold and wet day, normal weather for D.C. in mid-January. Likely as a result of the dreary weather, the number of attendees, estimated at approximately 300,000 (roughly the same as George W. Bush) fell below that of Obama, who’s first inauguration saw an estimated 1.8 million in attendance. But when Sean Spicer took to the podium the next day to deliver his first conference as press secretary, he insisted the crowd was “the largest audience to ever witness an inauguration, period.”

When asked about these provably false statements on NBC’s “Meet the Press” that weekend, Trump aide Kellyanne Conway insisted the press secretary didn’t lie—he had offered “alternative facts.” It was a phrase that perfectly captured the heart hallmark of the Information Age. Conway asserted a new political epistemology. There is not a single reality with two ways of looking at it; there are two realities.

Awed at Conway’s chutzpah, pundits noted the similarities between the Trump administration and the all-controlling government from George Orwell’s novel “1984.” He wrote: “The Party told you to reject the evidence of your eyes and ears. It was their final, most essential command.”

Truth vs. Profit

When Colleen Gay resigned as the president of Harvard shortly after Christmas, the national media was quick to frame her ouster as the result of two separate causes. The first was how she answered a question about protests on campus over the Israel-Palestine war. The second concerned charges of plagiarism on her academic record.

These were complex—and odd—reasons for a resignation. And the extent to which each influenced your understanding of what ultimately led to her removal depends on the media you consumed. As Ryan Holiday explains in his book, Trust Me, I’m Lying: Confessions of a Media Manipulator, everyone’s worldview is influenced by the way information is generated online. Unfortunately, that means that our media institutions are at the peril of market forces. “The economics of the Internet created a twisted set of incentives that make traffic more important—and more profitable—than the truth,” he wrote.

Throughout his tenure as the Director of Marketing for American Apparel, Holiday used these economic incentives to his advantage, finding surprisingly effective ways to sneak stories into major media outlets and bypass their fact checkers. But what scared him more than his success was discovering just how little fact checking mattered. It turns out that even when news outlets issued corrections about Holiday’s bogus stories, they didn’t change minds. In fact, people are more likely to think false claims are true after the claims have received a correction. Pandora can’t close the box.

In January 2017, Sean Spicer lied about the Inauguration crowd size to people who had, just hours before, witnessed the event and had hard data on the numbers. Was it merely a case of brazen dishonesty meant to frame his boss in a better light … or was this the opening shot of the War on Reality?

Whose Truth is it, Anyway?

To be clear, reality denial is not a right or left issue. Or rather, it’s both. Troll culture and cancel culture share the same DNA, according to Jonathan Rauch, author of The Constitution of Knowledge: A Defense of Truth. His research finds that all political factions have propaganda mechanisms that are “rooted in a sophisticated understanding of human cognitive and emotional vulnerabilities” and, crucially, use digital technology “to amplify their speed and reach.”

The human animal, like the wolf, survives through community. On some level, the most important decisions we make when assessing a new idea is whether it will help us socially. This is why, once an idea becomes central to our identity, it’s near impossible to change it. We don’t want to risk losing our social circles. The psychologist Daniel Kahan calls this “identity-protective cognition” and says it’s a bedrock component of the human psyche.

Imagine a good friend suddenly reversed all their opinions on every moral, economic, and social issue. Would this affect how much you want to hang out with them? They would be the same person, but chances are you’d want less to do with them. You would feel that they changed on a deep level, even if everything in their life remained the same.

If we can understand the same people as completely different people depending only on what they think, their minds—to some degree—shape our reality.

Is it Already Too Late?

Neuroscience research suggests that we believe something is true as soon as we understand it. If we see a pen sitting on a desk, we don’t question whether it’s real. We instantly accept that it is. Seeing is believing.

Something similar happens with ideas. If we read an assertion of fact, we immediately believe it as soon as we understand it. For example, if you read a news article stating a new species of shark has been discovered, you’ll believe this “fact” instantly. Most of the time, anyway.

Scientists have found there is a small window after we learn a new fact when we can teach our brains to “un-believe” it. Imagine seeing an outrageous headline, then glancing up to discover it was posted by the satirical paper The Onion. In this case, you’d immediately discount its veracity. This can happen with all facts—so long as doubt is introduced shortly after discovery.

Humans can train themselves to do this automatically, but it’s not easy. For years, experts have insisted the best defense against reality-denying news is a deep media training. They say we must learn to read skeptically. We must always be on guard for deep fakes and AI hallucinations. We must not believe our eyes and ears. It is their final, most essential command.

Luckily, there is another tract that is gaining scientific attention that may provide humanity with a pathway back to a shared objective reality. It’s part of a new vein of research called the Science of Attention, and it might provide our last, best hope to resist a deeply fragmented world.